A Renaissance man in 18th-century Utah

Friday, Jun. 13, 2014

'Miera y Pacheco: A Renaissance Spaniard in Eighteenth-Century New Mexico,' by John L. Kessell

+ Enlarge

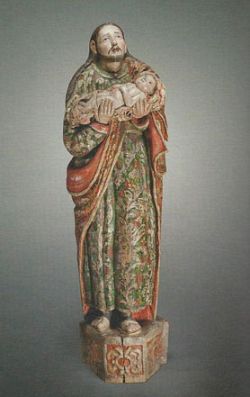

Among Don Bernardo de Miera y Pacheco's works is St. Joseph and the Baby Jesus, taken from 'Miera y Pacheco: A Renaissance Spaniard in Eighteenth-Century New Mexico,' by John L. Kessell.

Not well known even in his own day and less so in ours, Don Bernardo de Miera y Pacheco, cartographer of the Dominguez-Escalante expedition of 1776, is the subject of an excellent new full-scale biography, Miera y Pacheco: A Renaissance Spaniard in Eighteenth-Century New Mexico, by New Mexico historian John L. Kessell. The biography reveals a man of extraordinarily broad skills and achievements– a true Renaissance man.

Born in 1713 to a family of minor nobility in the northern Spanish province of Cantabria, Miera left almost no biographical details until he showed up in El Paso around 1740. We do have some good physical descriptions of him as an adult, and he was a man of striking appearance. He was very short, not quite five feet tall, with a thin nose, very light skin, blue eyes, and thick chestnut hair with full beard. The almost two decades he spent in El Paso were not financially successful: he invested in land, filed a claim on an unproductive silver mine, dealt in dry goods, and spent a dozen days in jail for nonpayment of a debt. Things started to improve when he moved to Santa Fe in the 1750s.

Ultimately it was his artistic talent that brought him success. Northern New Spain (the modern American Southwest) was poorly known to the Spanish government and subject to repeated problems with the various Indian tribes. Miera proved to be an excellent mapmaker, and was sent on multiple reconnaissance missions to produce a cartographic record of the realm. Kessell asserts that no one had covered more of the terrain of northern New Spain than Miera. But his maps are much more than just a cartographic record: they are true works of art. Marginal illustrations include the Pope in a carriage, renditions of the dress of indigenous inhabitants, and large blocks of text describing the nature of the terrain.

Miera was also a sculptor and painter who created impressive altar pieces and interior decorations for several mission churches. It was while preparing such decorations for the church at Zuni that Miera met Fr. Escalante, a paisano also from Cantabria, who was pastor of that desolate mission, the “Siberia” of New Mexico.

The Dominguez-Escalante expedition of 1776, which brought back the first detailed knowledge of what is now Utah, did so through two invaluable documents: the diary kept by the two Franciscan friars, and the Miera map. Vital though he was to the success of the expedition, Miera was a thorn in the flesh to the friars. He completely deserted the party for a time in Colorado because of its slow progress, he loudly objected to the friars’ decision to turn back to Santa Fe instead of trying to cross the mountains into California, and he irritated the friars by seeking treatment by a Southern Paiute medicine man for an intestinal disorder that was bringing him agony. Some of his ill temper may have been a factor of his age (he turned 63 during the trip) and frustration with his younger superiors (Escalante was younger than both of Miera’s sons), as well as his ill health.

Though he had his prickly side, Miera’s humanity was admirable. He never signed any of his maps, exhibiting a humility that causes him to stand out among the infamous egotists of the Renaissance. And, Kessell observes, although Miera participated in repeated expeditions against the Indians who were persecuting the Spanish colonists, he “had no trouble dealing with Indians as persons worthy of respect” – a trait that would have been remarkable anywhere on the western frontier.

Don Bernardo de Miera y Pacheco died in 1785, officially of natural causes, though his intestinal disorder may have indicated a chronic condition. His life had been remarkable. As Kessell puts it, Miera had “expressed himself artistically more notably, worn more hats, planned more projects, drawn more maps, known more Indians, and explored more [territory] than any other [New Mexican] before or after him.”

Don Bernardo helped get Utah history off to a fine start, and it is good that we can now know so much about him.

For questions, comments or to report inaccuracies on the website, please CLICK HERE.

© Copyright 2024 The Diocese of Salt Lake City. All rights reserved.

© Copyright 2024 The Diocese of Salt Lake City. All rights reserved.

Stay Connected With Us