New appreciation for Frs. Dominguez and Escalante

Friday, Apr. 08, 2016

During this year’s session of the Utah State Legislature, I testified, at the instigation of my colleague Jean Hill, before two committees on behalf of a bill sponsored by Rep. Mike Wheatley to commission and install on the Capitol grounds a statue commemorating the Dominguez-Escalante expedition of 1776.

The bill passed both committees without a dissenting vote – a consequence, I am certain, of the soundness of the idea rather than the persuasiveness of my testimony.

I took away two things from the experience: a heightened respect for the hard-working, conscientious and intelligent (for the most part) people who represent us. I will vote this fall with a new enthusiasm. The other thing I took away, as a result of my preparation, was a new understanding and respect for the Dominguez-Escalante expedition.

Few of us Utah Catholics, I think, are aware of more than that the first European explorers to enter the present area of Utah were Catholics and Spaniards. There is much more to know.

The two Spanish friars Dominguez and Escalante and their companions were not the first Europeans to enter Utah. We have records of two prior expeditions and there may have been others, but the compelling fact remains that their expedition was by far the most important such venture in western history before the completion of the Lewis and Clark expedition in 1806.

When they returned to Santa Fe in January 1777, the two friars brought with them an accurate map and a detailed diary that imparted to Europeans the first in-depth knowledge of any large portion of the trans-Mississippi West between New Mexico and California.

The expedition had two goals. One was to try to mitigate the isolation of New Mexico, at the far northern rim of the Spanish empire. It is some 1,500 miles from Mexico City to Santa Fe, a fact that, in the days of travel by foot and horseback, made the New Mexicans feel like they were living in a different world. That feeling of isolation was heightened by the fact that they were surrounded by large Indian tribes whose friendliness was precarious. Thus, the first goal was to try to locate an overland route from Santa Fe to Monterey, Calif., at that time the northernmost of the famous California missions. Such a route could open commercial relations and communication between the two communities.

The other goal, witnessed by the fact that the two leaders of the party were Franciscan friars, was to investigate the size and disposition of the population of indigenous peoples with the idea of opening missions among them.

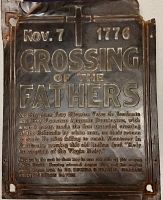

The party proceeded north from Santa Fe through western Colorado to a crossing of the Green River near modern Jensen, Utah. From there they journeyed westward through the Uintah Basin, through Strawberry Valley and Spanish Fork Canyon, where they encountered a large group of Indians at the shore of Utah Lake. They spent some time with them, sounding out their interest in having a mission established among them. Then they turned south, roughly along today’s Interstate 15 corridor, until they came near what is now Cedar City, at a latitude roughly corresponding to that of Monterey.

At that point a crisis developed: It was already mid-October and trying to cross the Sierras would be perilous. The friars wanted to head for Santa Fe, but the rest of the party, with their heads full of dreams of fortunes in business, wanted to continue. By means of a gambling apparatus, the choice was made to head for Santa Fe. They crossed the Colorado River near Lake Powell and returned home. They had been away for 159 days and had traveled some 1,700 miles.

In the end, the party failed in both its stated goals. Not only did they fail to locate an overland route to California, but they also found it impossible to establish a mission in Utah. Such a mission was simply too remote to find support either from the Spanish government or the Franciscan Order, especially since the expulsion of the Jesuits from the New World in the late 1760s, which meant that the Franciscans had to staff those missions as well as their own.

But in a larger sense, the expedition can hardly be considered a failure, for their map and diary provided rich data on topographical features, plants and animals, and indigenous peoples that made it possible for later explorers and traders to plan their own ventures. Eventually the Old Spanish Trail, based in part on the friars’ explorations, was an overland route from Santa Fe to Los Angeles and placed Utah at the center of a very lucrative international trade.

The Dominguez-Escalante expedition should be a source of pride for Hispanic Utahns and Utah Catholics, but their achievement belongs to all Utahns as well.

For questions, comments or to report inaccuracies on the website, please CLICK HERE.

© Copyright 2024 The Diocese of Salt Lake City. All rights reserved.

© Copyright 2024 The Diocese of Salt Lake City. All rights reserved.

Stay Connected With Us